A Premise Is Just *One* Reason, Not the Only Reason

One of the most important things to understand in logical reasoning is that an author’s premise is just *one* reason that they think their conclusion is true.

Now this idea is at its core quite simple, but failure to truly understand it often leads people to fall for trap answers.

Let’s explore two examples, starting with something more straightforward, and then moving to something more abstract.

Here’s my argument:

Now this idea is at its core quite simple, but failure to truly understand it often leads people to fall for trap answers.

Let’s explore two examples, starting with something more straightforward, and then moving to something more abstract.

Here’s my argument:

Since Tom Cruise is in Top Gun, it must be a great movie.

Am I assuming that Tom Cruise is the only reason that Top Gun is a great movie?

No, because I might also think that having exciting action sequences or compelling character interactions makes it great, too. So Tom Cruise doesn’t have to be the only thing that I think makes the movie great, he’s just one reason that I happen to give you.

No, because I might also think that having exciting action sequences or compelling character interactions makes it great, too. So Tom Cruise doesn’t have to be the only thing that I think makes the movie great, he’s just one reason that I happen to give you.

Now you might think … “But we can say that the argument is assuming Tom Cruise being in the movie is the main reason you think it’s great, right? His presence is the biggest factor in what makes the movie great, right?”

Actually no. He’s just one reason I think the movie is great, but maybe I think the action sequences are a bigger factor or the compelling character interactions are a bigger factor.

You might respond, “But why didn’t you mention the action sequences or other reasons that you think the movie is great?”

Because I don’t have to give you every reason I think I’m right. I don’t even have to give you my most important or best reason, as long as the reason I did give you is enough to prove my conclusion.

So what I am assuming is that the presence of Tom Cruise is sufficient, or in other words, enough by itself, to prove that a movie is great. But, I might have hundreds of *other* reasons to give you that I also believe prove the movie is great — I just don’t care to provide them to you right now, because I think you should be satisfied with the reason I already gave.

Now if you understand this idea, you can start to understand what makes wrong answers wrong across different question types.

For example, is this argument assuming that “If a movie doesn’t have Tom Cruise, then it’s not great”?

Of course not — I’m open to many other reasons that a movie could be great. I’m just saying Tom Cruise is one reason that makes a movie great, not the only one.

Could you weaken this argument by showing “Most movies that don’t have Tom Cruise are great”?

Again, no, I never said he’s the only reason that a movie would be great. You can have plenty of great movies that don’t have Tom Cruise — maybe they’re great for other reasons (Nicolas Cage) — I never suggested this wasn’t possible.

Actually no. He’s just one reason I think the movie is great, but maybe I think the action sequences are a bigger factor or the compelling character interactions are a bigger factor.

You might respond, “But why didn’t you mention the action sequences or other reasons that you think the movie is great?”

Because I don’t have to give you every reason I think I’m right. I don’t even have to give you my most important or best reason, as long as the reason I did give you is enough to prove my conclusion.

So what I am assuming is that the presence of Tom Cruise is sufficient, or in other words, enough by itself, to prove that a movie is great. But, I might have hundreds of *other* reasons to give you that I also believe prove the movie is great — I just don’t care to provide them to you right now, because I think you should be satisfied with the reason I already gave.

Now if you understand this idea, you can start to understand what makes wrong answers wrong across different question types.

For example, is this argument assuming that “If a movie doesn’t have Tom Cruise, then it’s not great”?

Of course not — I’m open to many other reasons that a movie could be great. I’m just saying Tom Cruise is one reason that makes a movie great, not the only one.

Could you weaken this argument by showing “Most movies that don’t have Tom Cruise are great”?

Again, no, I never said he’s the only reason that a movie would be great. You can have plenty of great movies that don’t have Tom Cruise — maybe they’re great for other reasons (Nicolas Cage) — I never suggested this wasn’t possible.

Let's use another example.

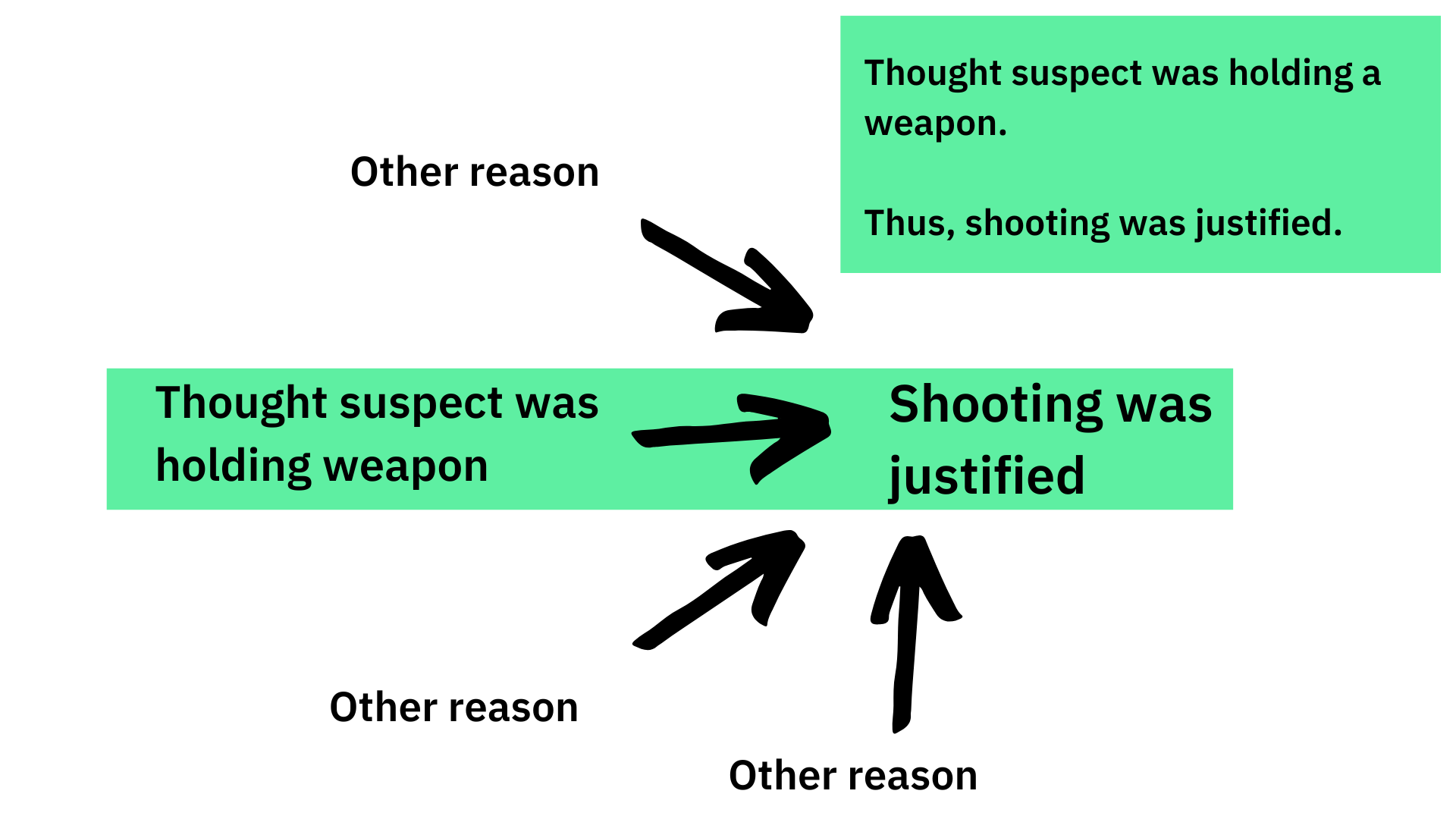

The officer’s use of force against the suspect was justified because he thought the suspect was holding a weapon.

Is this assuming that if a police officer does not think a suspect is holding a weapon, then use of force against the suspect is not justified?

Actually, no. Remember, the premise of the argument — that he thought the suspect was holding a weapon — is just *one* reason that the author thinks the conclusion is true. If you take away that reason, there could still be plenty of other reasons that the author thinks the use of force is justified. Although it might be hard to think about what those other reasons would be, it shouldn’t matter whether we personally can come up with other reasons that the use of force might be justified — we want to recognize just from the structure of the argument that there could be other unknown reasons that make it justified.

Actually, no. Remember, the premise of the argument — that he thought the suspect was holding a weapon — is just *one* reason that the author thinks the conclusion is true. If you take away that reason, there could still be plenty of other reasons that the author thinks the use of force is justified. Although it might be hard to think about what those other reasons would be, it shouldn’t matter whether we personally can come up with other reasons that the use of force might be justified — we want to recognize just from the structure of the argument that there could be other unknown reasons that make it justified.